Review: Ankit Panda and Frank Close offer little hope on managing nuclear threats

In The New Nuclear Age, Panda starts from where Close, in Destroyer of Worlds, concludes: “at the precipice of Armageddon”.

In his latest book, “Destroyer of Worlds”, Frank Close takes us back to the beginnings of the nuclear age and guides us through the decades that followed. His is a story of unintended consequences. What started in the late 19th century as a search for an understanding of the atomic foundations of life on Earth morphed into the power to end such life.

Ankit Panda in “The New Nuclear Age” starts from where Close concludes “at the precipice of Armageddon”. Neither book makes for comforting reading and Panda struggles to persuade – this reader at least – that strategic deterrence can keep on providing a genuine degree of security in what he terms a “third nuclear age”. Together, the two books suggest that sustainable peace is becoming ever more challenging to secure.

Himself a distinguished nuclear physicist and Oxford Professor, Close’s account has its heroes and – though far fewer – heroines. But when nuclear physics was taking shape as an academic discipline, the scientists involved found pushing the boundaries of knowledge irresistible whatever forebodings they might have had as to the attendant dangers. Only a few held themselves back having foreseen the likely consequences or over time came to rue what they had helped unleash. Close has crafted a well-paced, exciting narrative. Though many parts of the story have been told before, Close uses his skills as an historian as well as a physicist to pull it all together anew and in language accessible to the non-specialist reader. What he achieves is a revealing synthesis of a complex evolution, dovetailing theory and experiment en route to nuclear power and destruction in 1945.

Close reveals the deep history of the nuclear age not as a neat pathway from original scientific thought to practical attainment but as an often haphazard and chance trajectory. Roentgen’s discovery of X-rays in 1895 and Becquerel's of evidence of the release of nuclear energy one year later were more accidental or inspired than planned. And it was Marie and Pierre Curie in Paris shortly afterwards who made the key leap that established the radioactive intensity of key minerals, the purest form of which was in radium, a discovery that made diagnostic X-rays available and caused painful later-life injuries to the Curies themselves.

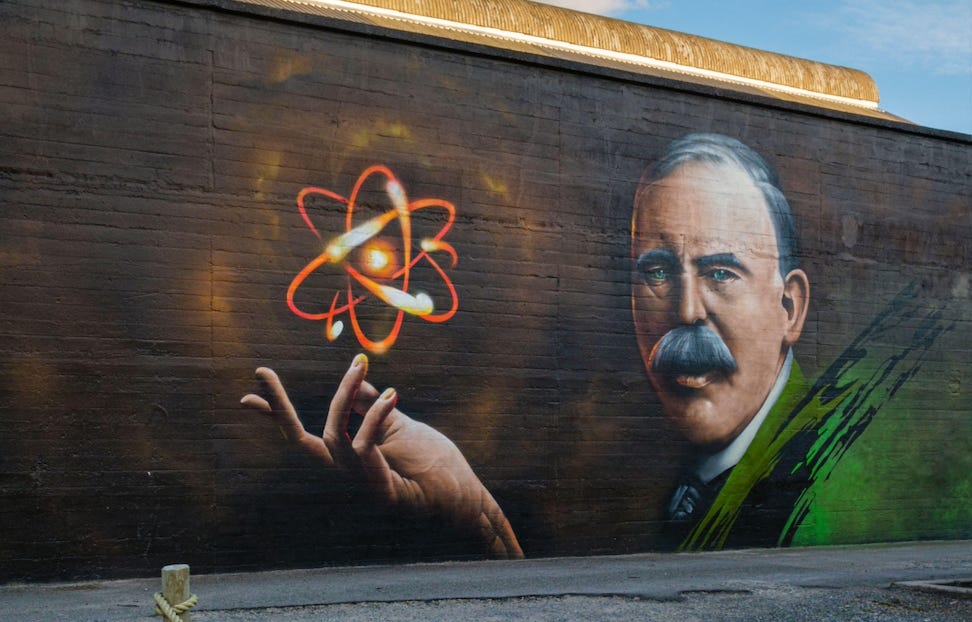

But it was the man from New Zealand, Ernest Rutherford, who most clearly realised in the years before the First World War that the discovery of radioactivity in the atoms of an increasing number of elements suggested the truly astonishing intuition that atoms were not as hitherto thought the stable and fundamental seeds of all matter but the repository at the sub-atomic level of huge levels of constrained energy.

From Rutherford and his colleagues at the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge, the journey towards realised – theoretically unlimited – levels of liberated atomic energy accelerated at great speed. Close shows clearly how the science developed incrementally in a number of key centres of expertise in Germany and Italy as well as France, England, Canada and, eventually and decisively, the United States.

Until the 1930s and the looming possibility of a second world war, the scientists were stirred by the search to be first, to win Nobel Prizes and to re-shape fundamental scientific understanding; but the rise of fascism and the increasing awareness that atomic energy could be utilised as a weapon of destruction, introduced different and more nationally denominated goals.

Close attentively examines the awesome possibilities and risks that the scientists’ experiments were exposing and often facilitating. And he carefully explores the dilemmas and issues of conscience that many of the scientists faced as they proceeded along a road in which research laboratories were intersecting uncomfortably with political ideologies and the orchestrators of war.

Even in the years before the outbreak of war, a few notable individuals held back; others would do so in the course of the war; whilst others would be increasingly troubled in the post-war years as the implications of the burgeoning availability of nuclear weapons affected them profoundly. Some scientists though seemed infatuated with the scientific powers and possibilities they had helped unleash - most conspicuously, Edward Teller, who sought ever greater nuclear, indeed thermonuclear, weaponry.

As Close remarks:

“In 1896, the first pointer to nuclear energy had been so insignificant that it was almost missed. Within seven decades this has led to the explosive power of 'Tsar Bomba' [the 100 megaton device devised for testing by the Russians during the Krushchev years], the greatest ever recorded other than the meteorite impact sixty-five million years ago that wreaked global change and killed the dinosaurs. The dinosaurs had ruled for 150 million years. Within just one percent of that time, humans have produced nuclear arsenals capable of replicating such levels of destruction. The explosion of a gigaton weapon would signal the end of history. Its mushroom cloud ascending towards outer space would be humanity’s final vision”.

After taking the reader along the scientific path to the successful detonation of a nuclear device in the New Mexican desert in 1945 and the subsequent use of the new weapons over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Close points up in turn the nuclear weapons scientists he most admired – his seeming heroes – who questioned the road ahead immediately before, during and after the Second World War.

He cites first the integrity of the exceptionally brilliant young Italian physicist, Ettore Majorana, who having intimated the prospect of nuclear weapons wanted nothing more to do with such work and disappeared – whether by suicide or re-location incognito in South America – after a flight to Palermo in March 1938 as a rare instance of objection by a nuclear scientists before the war. He then highlights the singular withdrawal of the British-Polish physicist, Joseph Rotblat, from the Manhattan Project once he was told Germany had surrendered; for Rotblat with Nazism defeated there could be no ethically admissible justification for actual use of the new weapon. And Close then touches on the post-war nuclear scientists intent on limiting further development, let alone use, of ever more powerful nuclear weapons, most notably Andrei Sakharov who bravely and insistently sounded the alarm in the Soviet Union and helped realise the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty in 1963.

Close, the nuclear physicist, signs off his narrative in 1965. Ankit Panda, the political scientist, turns his readers attention to present day nuclear prospects and risks. His title and analysis suggest we are now in a new nuclear age; but that is far from clear. The elements present since the 1950s are still determinant. Nuclear arsenals continue to evolve and grow. To the original nuclear powers – the US, Soviet Union and UK – were several decades ago added the newer ones of China, India, France, Pakistan and Israel. Others have joined them in breaking the nuclear taboo – North Korea – or in the case of Iran, threatening to do so. Even the decline in negotiated nuclear arms control treaty isn’t new.

What is new as Panda recognises and analyses is a mix of increasingly unstable factors. First, evolving strategic nuclear relations as China grows its nuclear capabilities and upsets the previous essential duopoly between the US and (now) Russia. Secondly, the possibility of further nuclear break-outs if Iran turns its nuclear potential into nuclear weapons. And, thirdly, worryingly novel new technologies being applied to nuclear weapons alongside possible sub-strategic use (as threatened at one stage by Russia in Ukraine) and increasingly sophisticated outer space deployments.

Unavoidably in a book written between 2022 and 2024, Panda eludes to the impact of the election of Donald Trump. Patterns of already existing complexity in international relations have been made increasingly unpredictable as the war in Ukraine continues and assumptions about the reliability of extended deterrence by the US for its long-time allies in Europe and East Asia weaken.

Strategic stability requires high levels of predictability and it is precisely that dimension which has declined. In his search for a positive way forward as global nuclear patterns re-shape and complexities grow, Panda offers only limited hope that international arms control measures can continue to constrain proliferation. In the main, he puts his limited trust in the “fear” of nuclear use continuing to hold nuclear states back from actual use. In other words, he hopes nuclear deterrence will continue to provide a kind of stability.

As I indicated at the beginning of this review this reader at least is not convinced that fear of nuclear use, potent as that taboo has hitherto remained, is a sustainable longer-term basis for international security.

Destroyer of Worlds: The Deep History of the Nuclear Age:1895-1965 by Frank Close, June 2025, Allen Lane, £25

The New Nuclear Age: At the Precipice of Armageddon by Ankit Panda, February 2025, Polity, £25