Children of Radium is wry, occasionally sour and deeply laced with tragedy

Joe Dunthorne’s exploration of the life of his great-grandfather is akin to a miniature portrait in the midst of a wider Nazi landscape.

There can be few more arresting opening lines: “My grandmother grew up brushing her teeth with radioactive toothpaste.” That sentence sets the tone of Joe Dunthorne’s new book as a whole: wry, occasionally sour and deeply laced with tragedy.

“Children of Radium” is the unexpected outcome of Dunthorne’s excursion into the 20th century history of his own family. Or at least into the German part of his family. For hidden behind the Welsh novelist’s surname is his other family name, his mother’s maiden name, Merzbacher.

Though herself born in Britain, her own mother left Nazi Germany with other members of her Jewish family in the mid-1930s. Neither Dunthorne’s mother or – especially – his grandmother were keen to delve into the family’s past. But his great-grandfather, Siegfried, had been long intent on writing a memoir which his brother eventually translated into English shortly before his own death. Hundreds of pages long, it was, as Dunthorne came to realise, a sort of extended prologue which kept promising to deliver the full story but never quite managed to get to the difficult bits. And from a post-war perspective, Siegfried had some explaining to do.

What emerges from Dunthorne’s almost ruminative exploration of the life of his great-grandfather is akin to a miniature portrait in the midst of a wider Nazi landscape and its aftermath. What Dunthorne unearths with varying degrees of certainty is indeed as the subtitle of his book describes it, “a buried inheritance”.

Though centred principally on his great-grandfather’s ambivalent behaviours and self-deceptions, the Merzbachers had another family member, Siegfried’s sister Elizabeth, whose care for Jewish children in 1930s Munich sets a nobler counterpoint to Dunthorne’s account of his great-grandfather.

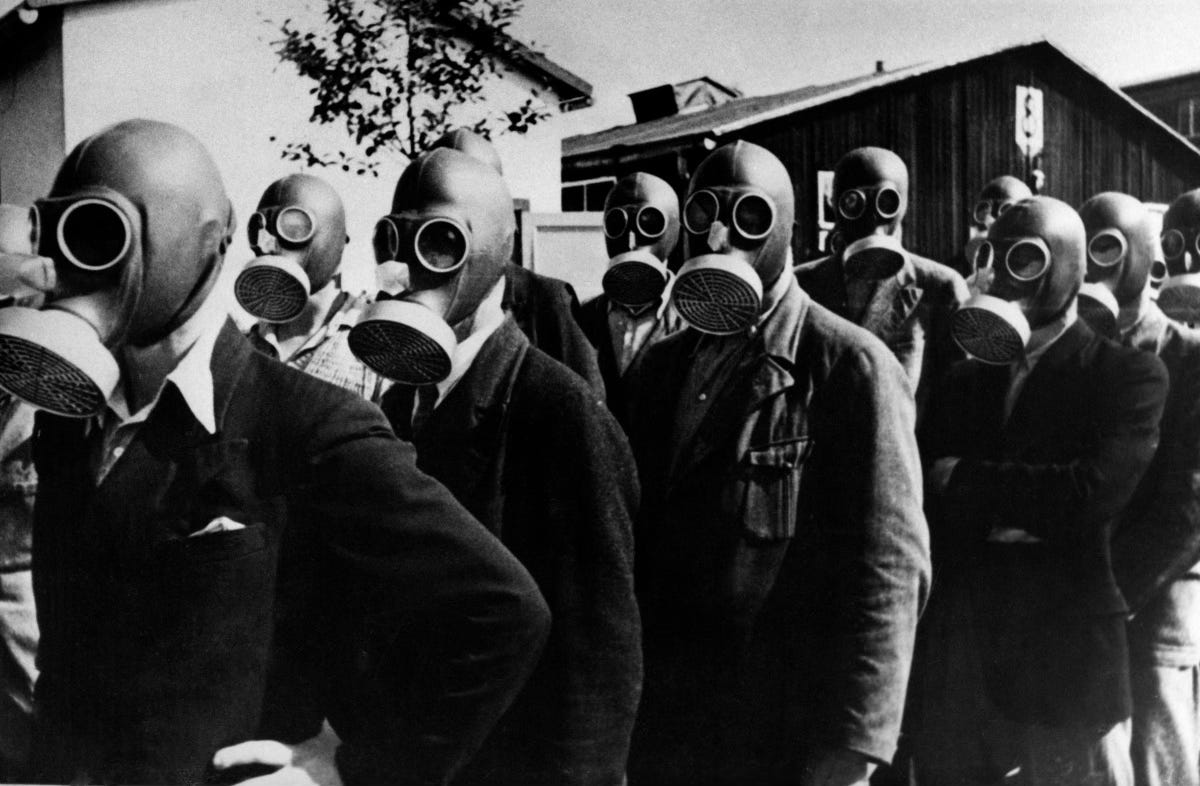

Siegfried Merzbacher was a chemist who helped make the radioactive toothpaste which accompanied his family when they left Germany and which was later supplied to German soldiers during the Second World War. Less innocent was Siegfried’s pre-war role in the development of masks to protect against chemicals used as weapons (CW). At the least he worked knowingly and co-operatively alongside colleagues in secret laboratories north of Berlin where horrifically deadly CW agents were refined for possible use as weapons.

Flattered into helping sustain, even if only indirectly, the Nazi's CW programme – of which protective masks were a part – he became as a Jew increasingly anxious for himself and his family. He grabbed an opportunity offered to him by his own boss of a kind of secondment to Turkey. Away from the Nazi menace, he and his wife and children thought they were in clover till his old boss at the chemical weapons laboratories in Germany came calling on him in Ankara.

Drawn into the Nazi web once more, Siegfried became involved in the provision of protective masks licensed by the Germans for use by the Turkish security forces. Dunworth’s digging into this Turkish dimension of his great-grandfather’s life is especially unsettling. In 1937-1938, the Turkish authorities in Ankara determined to suppress continuing resistance from Kurdish Alevis in the mountainous east of the country. There in the area around a small town in Dersim, repression turned into a genocide. News of the massacre was kept secret or simply denied until acknowledged by the Erdogan government in 2012.

But sensitivities remained as Dunthorne discovered during his journey to the remote area. What he established was that the masks his great-grandfather had helped develop and which were sold to the Turkish authorities partly by his agency in the mid-1930s, were employed to protect troops who used poison gas or chemical weapons (possibly, we infer, supplied by the Germans as well) to snuff out resistance even deep in mountain caves. The official Turkish figures state that 13,160 civilians died in this way, though some historians suggest a very much larger number of dead.

For Dunthorne, the discovery of the Dersim massacre and his great-grandfather’s role in the provision of the protective masks was deeply disturbing. Using various hospital and other records in the US where Siegfried initially settled after the war, Dunthorne continued to seek a closer understanding of the role played by his great-grandfather in Germany before the war as well as in Turkey during it.

Siegfried’s incomplete memoir was silent or evasive on these points. What Dunthorne did find was evidence of Siegfried’s post-war clinical depression and of psychiatric treatment suggesting some unresolved personal – including possibly family – traumas. Even with such medical evidence to hand, the extent of pre-war and wartime culpability on his great-grandfather’s part remained unclear. What was clear was that Siegfried’s past activities in Germany and Turkey were murky, arguably made so in part by Siegfried himself who had declined to tell a full story, not just the prologue to it, in his memoirs. How far he was self-deceiving as much as just evasive, was impossible for Dunthorne to assess with any authority.

From the outset of his family explorations, Dunthorne was aware of the circumstances of their departure from Germany in 1935. What he was much less aware of was the role of his great-aunt, Siegfried’s sister Elisabeth, and the other women who provided a place of care and safety for Jewish children in Munich.

For whilst Siegfried and his wife and their immediate family were safe in Turkey, Elisabeth – Dunthorne’s great-aunt – was still in Munich and engaged on what would prove an altogether different and courageous activity. Responding to the increasingly precarious circumstances of mainly Jewish refugees from persecution in countries further east, Elisabeth with her assistant Lilli was instrumental in the setting up of a Kindergarten in central Munich. They moved premises so as to be able to cater for more children – not all of whom were Jewish, at least initially. However, facing increasing Nazi pressures to close the nursery down and with her own husband Wilhelm temporarily incarcerated at Dachau, Elisabeth eventually decided that after the attacks on Kristallnacht in November 1938 and attacks on her personally including forcing her out of successive apartments, she and Wilhelm should leave the country.

Later that year, they arrived in Tel Aviv. Elisabeth maintained contact as long as she could with the two Jewish colleagues she had left behind to manage the Kindergarten, Alice Bendix and Hedwig Lamar. These truly heroic women whose brief pen-portraits written later by Elisabeth are included in Dunthorne’s account, remained caring for the declining numbers of children in the nursery and in the midst of the war accompanied the final few on their journey to Auschwitz. There the two women provided what comfort they could for the children in their final days and died with them in the gas chambers.

As one comes towards the end of “Children of Radium”, this reader was inclined to agree with Dunthorne’s mother's query as to whether he had chosen to write about the wrong sibling and that the focus should have been rather more on Elisabeth than Siegfried.

However, part of the strength of Dunthorne’s book is that it is not driven by judgment as by a search for his family's complex but uncertain past. How far Siegfried was complicit in Nazi development of CW and the Turkish attacks in Dersim is far from clear in part because Siegfried remained reluctant to pose the question to himself before his death in Edinburgh in 1971. Elisabeth’s care for children in Munich seems altogether clearer.

In the end the emblematic figures in Dunthorne’s story are not Siegfried or Elisabeth but Alice and Hedwig, the women who stayed with the children in their care until their deaths alongside them in a gas chamber.

Meanwhile, those who administered the poisons that killed them were probably themselves protected by masks developed originally by Siegfried Merzbacher.

Children of Radium by Joe Dunthorne, Hamish Hamilton, April 2025, £16.99